What if we told you that Montana’s compacting process pretty much ensures that none of the State’s federal reserved water rights compacts have been judicially reviewed on their merits, but rather have been based upon something called a consent decree standard of review?

What if we also told you that the hearing track of the water compact review will not allow the water court or other courts to which a decision is appealed to be determined upon the merits of the issues within the compact itself?

“In reviewing a consent decree, a court must be satisfied that the settlement is at least fundamentally fair, adequate and reasonable, and because it is a form of judgment, a consent decree must conform to applicable laws. The review and resulting decree is not a decision on the merits or the achievement of the optimal outcome for all parties, nor must it impose all the obligations authorized by law. Rather, it is a limited review, the extent and limitations of which have been described by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.”

The Montana Water Court has adopted the rule employed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in reviewing consent decrees, which is that once the court is satisfied that the settlement was the product of good faith, arms-length negotiations, a negotiated settlement, is presumptively valid, and the objecting party has a heavy burden of demonstrating that the settlement is unreasonable. This presumption is particularly appropriate where government actors committed to the protection of the public interest have pulled the laboring oar in constructing the proposed settlement.

Source: In re Adjudication of Existing and Reserved Rights of Chippewa Cree Tribe, The Water Court of the State of Montana, June 12, 2002, Filed CASE NO. WC-2000-01

There you go. The court assumes that our three “government actors” were committed to the protection of the public interest when they “negotiated the Flathead Compact.

In other words, based upon the water court’s consent decree review of the other 18 water rights compacts, the compacting parties knew that once the compact was “ratified” in the Montana legislature it would be assured that the compact would very likely not ever be reviewed on its merits.

This explains why the water court always seems to have “rubber stamped” the water compacts. Without a solid understanding of the Water Court’s standard of review, the objectors never had a real chance.

It also focuses some light as to the reasons why some members of the Compact Commission and the Montana legislature willfully colluded with the tribes to change house rules in order to ratify the compact in the 2015 Montana legislature.

Over the years, we’ve worked hard to provide charts, data, and other factual information to the public concerning the Flathead Water Compact, and even the 10,000 claims that were filed for the purpose of coercing water court approval of the compact. We felt strongly that if legislators saw the truth of the compact there is no way that it would be ratified by the state.

It is and has always been a very honest and effective approach.

Unfortunately, we were naïve in not realizing the great extremes that the compacting parties would go to in order to garner the compact’s ratification in the legislature.

After the compact failed in the 2013 legislature, had the normal political process played out, it would also have failed in 2015. Unfortunately for the people of Montana, that is not what happened.

The level of corruption within Montana’s political class is truly astounding. But then again, we are talking about water resources worth billions, if not trillions of dollars, not to mention the control the federal government and tribes could exert over people and their property.

What is unexplainable, is why Montana would willingly ignore its own best interests and those of its citizens. The compact is so unfair and lopsided, that it reaches the level of unconscionability.

The “Merits” of the Case

“On the merits” refers to a judgment, decision, or ruling that a court will make based on the law, after hearing all of the relevant facts and evidence presented in court.

Source: https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/res_judicata

We equate the notion of having your day in court as having it heard on its merits, specifically: Points of Fact and Points of Law.

Sadly, in this day and age, cases are rarely ever heard on their merits. The rule of law and the constitution rarely rule the day anymore. See: No More Kicking the Can Down the Road

For as much as Obamacare forever changed “healthcare,” our legal system has also significantly changed while the people who believe they have a constitutional right to be heard in a court of law weren’t paying attention.

The reality is that most cases are dismissed well before a dispute or lawsuit ever gets into the facts of the case and legal issues are presented. This is because the courts have contrived all kinds of things that preclude people from ever having their day in court.

Contrivances could be such things as forcing litigating parties to go through mediation or arbitration. Another tact used in the courts are MOTIONS TO DISMISS based upon a whole host of technicalities. We see this as the legal system as distancing itself from the people.

You can rest assured that at least a few of these roadblocks will be used by the compacting parties during the Montana Water Court hearings and other legal proceedings going forward.

- Lack of legal standing – Standing is not about the issues, it’s about who is bringing the lawsuit and whether they have a legal right to sue.

- Lack of subject-matter or personal jurisdiction – Does the court have the authority to make a binding decision over all the parties involved in a lawsuit, and to hear cases of a particular type or cases relating to a specific subject matter.

- An improper venue (location for the case) – proper venue is just as important as establishing a court’s jurisdiction. A case filed in an improper venue faces the threat of being dismissed or transferred.

- Insufficient service of process – did the plaintiff (petitioner) send the court summons, and a copy of their complaint to the defendant (respondent) directly?

- Failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted – If this is alleged, the courts usually don’t look at documentary or other evidence at this stage and merely review the complaint itself to see if a claim has been made.

While many people believe the issue is that it is too expensive to hire an attorney, the reality is that “even those individuals who can afford counsel rarely get their day in court. Rather, in the overwhelming majority of cases, they settle with their adversaries before the merits of their cases ever get heard. This is true even in federal courts, where, because of lighter dockets, there is much less institutional pressure to settle. Nevertheless, whereas in 1938 about 19 percent of all federal civil cases went to trial, by 1962 that rate had declined to 11.5 percent and by 2015 it had declined to an abysmal 1.1 percent.

Although the data for state civil cases are less ample, it appears that in state courts the situation is even worse, with fewer than 1 percent of them now going to trial.“

And while it is true that some of the remaining 99 percent of cases are resolved by motions made in court and accepted by a judge, in the majority of cases the parties simply settle without any judge or jury reaching a decision on the merits.

Source: New York Review, Why You Won’t Get Your Day in Court, Jed Rakoff U.S District Judge, November 25, 2016

This information is important for objectors to the Flathead to know as they get ready to prepare for battle in the hearing track of the Water Court proceedings.

Objectors must be smart about how they move forward, and prepare for the onslaught of motions to erase and diminish every last objection to the compact.

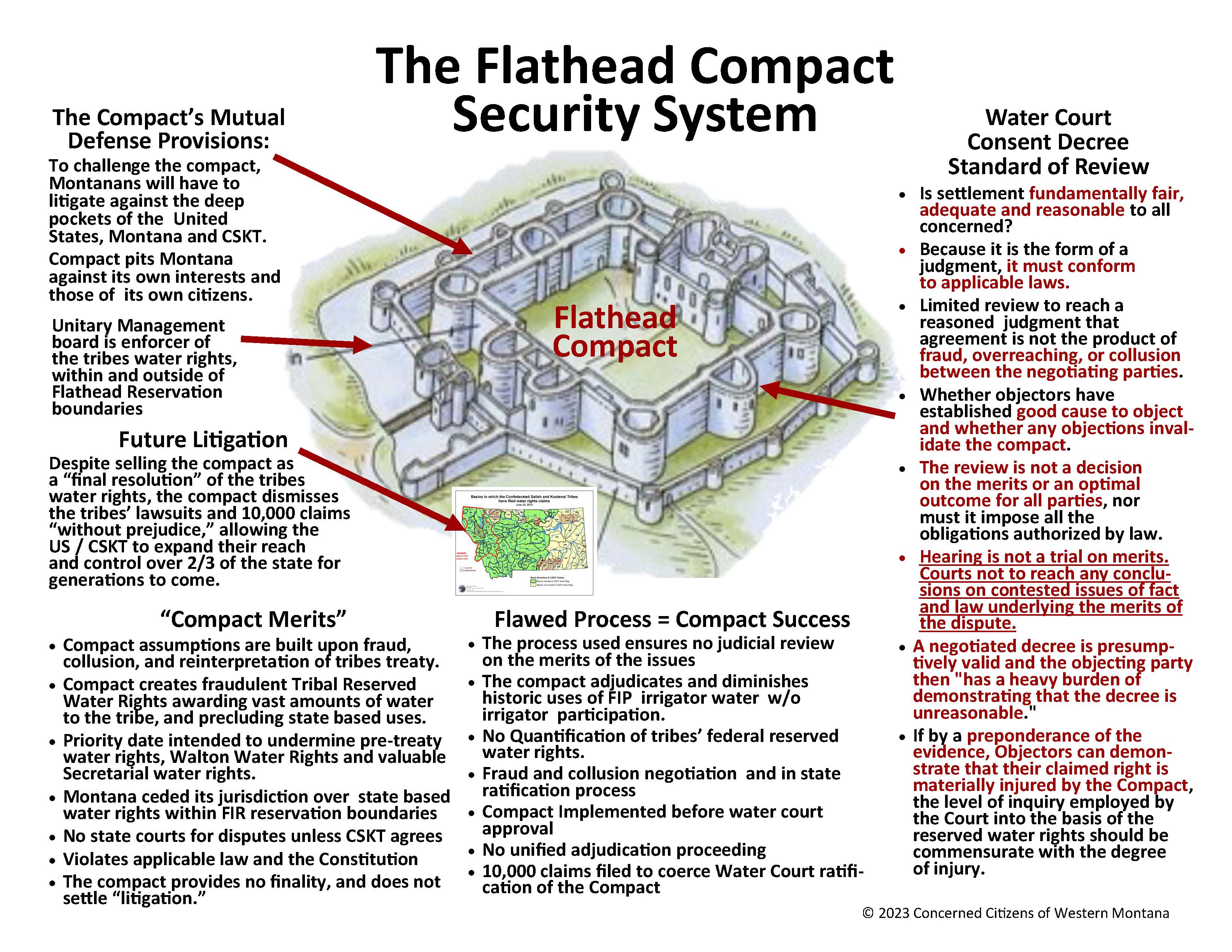

The Flathead Water Compact Security System

As you know, some of our previous posts have discussed the term lawfare in the context of the Flathead Water Compact.

Legal warfare, also known as lawfare, is the use of legal systems and institutions to damage an opponent or to deter or restrict an individual’s use of their legal rights and constitutional protections. It also describes a tactic used by repressive regimes to discourage or prevent individuals from protecting their legal rights via the legal system.

The Water Court’s consent decree standard of review is just one of the ways the compact is protected from serious scrutiny.

We could go through the litany of provisions of the compact that demonstrate the compact’s use of lawfare to protect it from all attacks, however we think this chart may do just as well. Click on the picture below for a pdf version of this chart.

Preparing for the Water Court’s Standard of Review

We ask objectors and the general public to prepare for the water court’s CONSENT DECREE review of the compact. The Water Court has already told us that it will presume:

- That the interests of the public were represented and considered by the compact commission in the “negotiation” process.

- That the legislature reviewed the compact on its merits before it voted

- That the government compacting parties would not negotiate a settlement that violates the law, the constitution or the property rights of the people affected by it.

However we know of the fraud within the compact and the collusion that took place during the 2015 legislature to garner legislative ratification of the compact.

See: Bruce Tutvedt: CSKT Lobbyist or Legislator?

We also know from a show of hands at the Montana house hearing on the compact that nearly all of the legislators had not read the compact. How could the legislature have reviewed the compact on its merits if they did not read it?

The Water Court also understands that it cannot approve a consent decree that does not adhere to the laws and the constitution: In reviewing a consent decree, a court must be satisfied that the settlement is at least fundamentally fair, adequate and reasonable, and because it is a form of judgment, a consent decree must conform to applicable laws.

The compact clearly violates the applicable laws pertaining to federal reserved water rights settlements. It also contains numerous other violations of the laws and constitutions of the United States and the state of Montana. The sheer overreach in terms of volume of water and priority dates, as well as Montana’s cession {the illegal assignment of its authority and property to another entity} of its jurisdiction for many state based water rights holders, render the compact so unfavorable to the State and its citizens that it can only be seen as unconscionable.

See: The Fraud of Tribal Reserved Water Rights

This makes it incumbent upon the objector to decisively and clearly show the violations of the law represented in the compact, however it must be done within the context of the Water Court’s guidelines and instructions, as well as the rules of civil procedure.

Objectors can’t just say that the compact is unlawful and unconstitutional, they must articulate it in such a way that the water court is unable to turn a blind eye to it.

The court may very well turn a blind eye to every objection, quite dismissively; but that must be suffered, to maintain in the court recordings that such objections were made … grounds for appeal.

Please use your very extensive knowledge of the water compact to present this to the Pacific Legal Foundation.

“PLF attorneys provide pro bono legal representation, file amicus curiae briefs, and hold administrative proceedings with the stated goal of supporting property rights…”

They have standing with the US Supreme Court and have won cases.

It has taken many of us a year or more to understand what Judge Brown said in the Water Courts first Order back in June 2022. In layman’s terms, the Water Compact has been deemed by the MT State Water Court as a consent agreement amongst the three parties, merit is presumed and will not be an issue before this court. Get Over it, this is the way we have adjudicated all the other Tribes agreements and cited Chippewa Cree Tribe and Blackfeet Tribe as analogous.

I totally agree with your comment that our legal court system has developed “contrivances” to distance itself from the people! I think bureaucracies have followed that same pattern as they are so bold as to legislate by rules and regulations. The Executive Branch under Obama started the trend of “try anything” and see what happens. While whatever will happen is decided we can do what we can never get done in the legislature. Biden admin has used this at a much faster and bolder pace.

In reviewing a consent decree, a court must be satisfied that the settlement is at least fundamentally fair, adequate and reasonable, and because it is a form of judgment, a consent decree must conform to APPLICABLE laws.

Note the word APPLICABLE. In the case of the Fort Peck water compact, the state pointed only to the Montana Statutes as being applicable. In the state’s motion for summary judgment in the Fort Peck Compact case, the attorney general said this:

The Compact Was Reached in Accordance With and Otherwise Conforms to Applicable Law.

Montana Code Annotated § 85-2-701 sets out three conditions precedent to the submission of a water rights compact to the water court for approval and incorporation into the adjudication. First § 85-2-701(1) requires that negotiations must be “commenced by the commission.” Id. at (1). The affidavit of Scott Brown establishes that negotiations were commenced <in 1979. (Brown Aff., % 3.)

Second] § 85-2- 701(2) provides that a compact must be agreed to by the Commission and the involved tribe, approved by the "appropriate federal authority," and copies filed with the United States Department of State, the Secretary of State of Montana, and the Tribe. The Compact was approved by the Compact Commission on April 5, 1985, and copies thereof have been filed with the required officials in accordance with that provision. (Brown Aff., .H 15.) The memoranda in support of this motion which will be filed by the Tribes and the United States will similarly establish their respective approvals of the Compact.

Lastly, § 85-2-701(2) provides that the Compact must be ratified by the Montana Legislature. As discussed earlier, the Compact was ratified by the Montana Legislature in 1985. 1985 Mont. Laws, Ch. 735, § 1.

All of the conditions precedent enumerated in Mont. Code Ann. § 85-2-701 have been met.

The Compact Represents a Fundamentally Fair, Reasonable and Adequate determination of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Water Rights.

Mont. Code Ann. § 85-2-235(7) requires that with respect to a reserved water right a final decree and by inference a compact must state:

(a) the name and mailing address of the holder of the right;

(b) the source or sources of water included in the right;

(c) the quantity of water included in the right; [and]

(d) the date of priority of the right;

(e) the purpose for which the water included in the right is currently used, if at all;

(f) the place of use and description of the land, if any, to which the right is appurtenant;

(g) the place and means of diversion, if any, and

(h) any other information necessary to fully define the nature and extent of the right, including the terms of [the] compact [] .

See also Mont. Code Ann. § 85-2-243(5). The Compact addresses each of these elements in a manner that has a basis in law and fact, and which is otherwise reasonable and equitable.

Was it intentional that the attorney general left out any discussion federal law and policy related to the federal reserved water rights in the Winter's Doctrine as part of "applicable law"?

Also we must ask if the attorney general's analysis of the fundamentally fair, reasonable and equitable test even passes the common sense sniff test?

Really? Just putting an abstract on paper, makes it fundamentally, fair, reasonable and equitable?

Did the water court actually do its own analysis of the Fort Peck claims, or were these statements intended to give the water court plausible deniability, making it possible for the water court to avoid actually reviewing the compact to determine whether the Fort Peck Compact met fair, reasonable and equitable test?

Who gets to define the terms fundamentally fair, reasonable and equitable?

In the case of the Flathead Compact, surely it cannot be the people that overreached and have fraudulently attempted to give it the cover of a federal reserved water rights settlement?

We know from the water court has said that they do not look at the merits of the agreement, or at least they will not rule on them because of the Consent Decree Standard of Review.

A copy of the Montana Attorney General's Memorandum in Support of the State's Motion to dismiss objectors and to approve the Fort Peck Comact can be found at this link:

Click to access 1997-02-28-fort-peck-ag-memoradum-in-support-of-motion-to-dismiss-objections-and-approve-compact.pdf