© 2023 Concerned Citizens of Western Montana

Ex post facto is a Latin phrase that essentially means “retroactive,” or affecting something that’s already happened. Such laws can change the consequences for actions that occurred before a law went into effect.

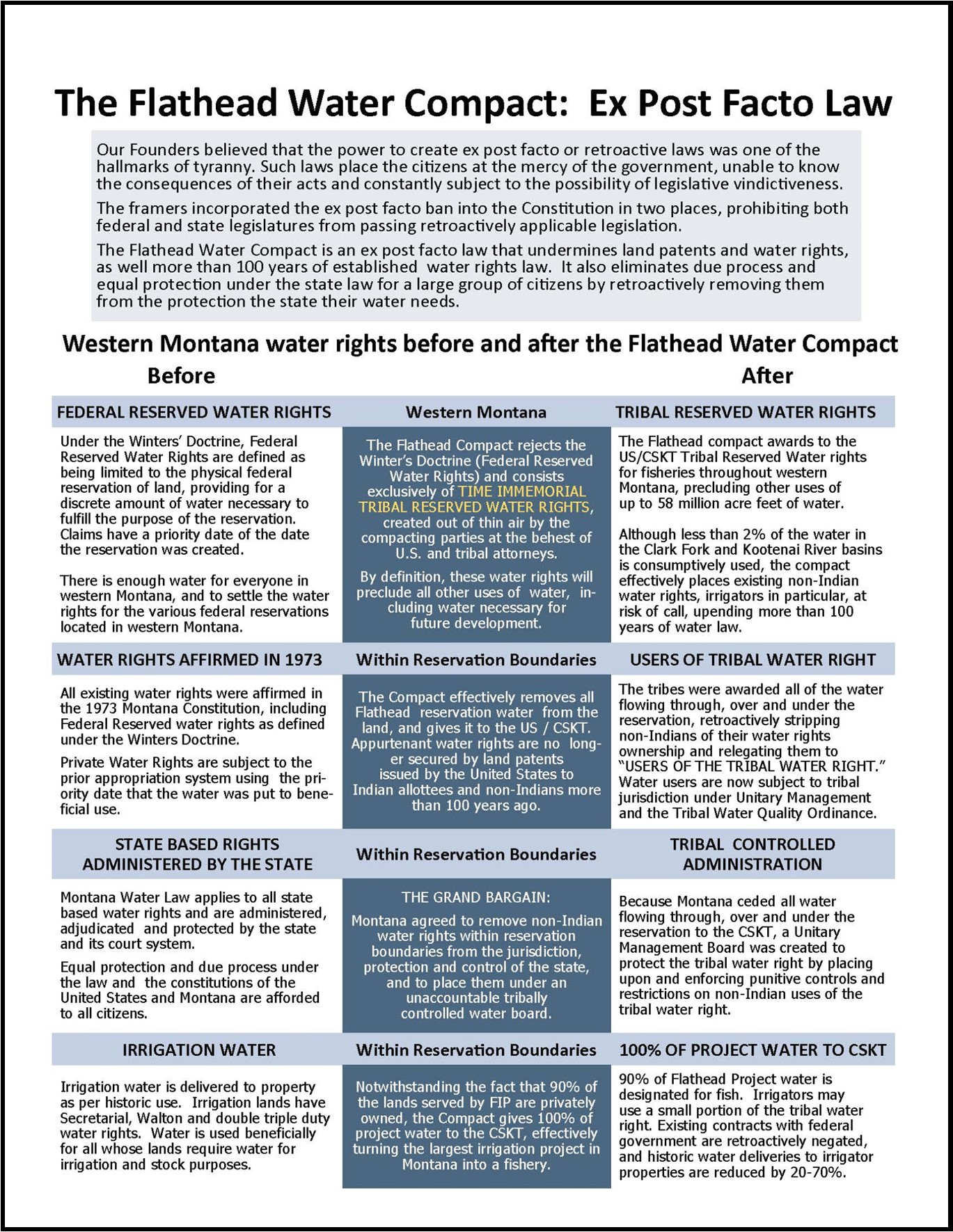

Our Founders believed that the power to create ex post facto or retroactive laws was one of the hallmarks of tyranny. Such laws place the citizens at the mercy of the government, unable to know the consequences of their acts and constantly subject to the possibility of legislative vindictiveness.

In our case, the Flathead Compact is not only a striking example of such legislative vindictiveness, it clearly demonstrates the ignorance and weakness of the elected officials that allowed a small tribal government to wreak havoc over the lives of the people in western Montana.

The framers incorporated the ex post facto ban into the Constitution in two places, prohibiting both federal and state legislatures from passing retroactively applicable legislation:

- Article 1, § 9 – Prohibits Congress from passing any laws which apply ex post facto.

- Article 1 § 10 – Prohibits the states from passing any laws which apply ex post facto.

Over the years, the courts have migrated the application of these ex post facto prohibitions to criminal law, however it is every bit as applicable to civil law statutes.

Is the Flathead Compact Ex Post Facto Law?

Absolutely.

The Flathead Water Compact settlement and legislation that is now codified into Montana Statute as 85-20-1901 (Compact) and 85-20-1902 (Unitary Management Ordinance) are perfect examples of ex post facto law. The compact is also a three amigo government agreed to, ex post facto rewrite of the history of the settlement of western Montana.

When you consider the devastating effect that the compact will have on property and water rights, and the massive transfer of wealth implicated within the compact’s details, it’s easy to understand that it represents the extinction of a major sea change with respect to federal reserved water rights. The compact negates federal reserved water rights and replaces them with artificially created time immemorial tribal reserved water rights.

There can be no doubt that the compact was intended have a resounding negative effect on property and water rights throughout the western United States.

In one fell swoop, the water and property rights rug was pulled right out from under the people who were counting on the state to protect its own interests and those of its citizens.

The compacting parties agreement to “tribe immemorial aboriginal water rights” retroactively ensures that there was no unconstitutional taking of the water and property rights of western Montanans because the compact says the water that we’ve been using for more than a century was reserved by and has always belonged to the tribe.

Does anyone really think that people would have purchased land and settled in western Montana had they thought that the tribe would own and control the water that is appurtenant to their property?

Such is the tyrannical nature of an Ex Post Facto law.

The Flathead Water Compact is a perfect example as to why a constitutional prohibition against ex post facto laws was necessary.

The compact begins with a rewrite of the July 16, 1855 Treaty of Hellgate (12 Stat. 975). By claiming the tribe reserved the reservation, and not the United States, the compact rejects what was supposed to have been the quantification of federal reserved water rights of the Flathead Reservation based upon the purposes for which the United States reserved the land. Once quantified, these water rights were also supposed to carry an 1855 priority date.

The compacting parties then used their misrepresentation of fact to negate the reservation’s federal purpose of individually allotted home lands as specified in ARTICLE VI of the treaty. Once the “federal reserved water rights” were voided, the compacting parties fraudulently inserted an aboriginal tribal fisheries’ purpose in its place.

This shift makes Flathead Water Compact an ex post facto law that undermines and effectively reverses policy and legal consequences of retroactive changes in laws related to:

- The 1904 Flathead Allotment Act which initiated the federal fulfillment of ARTICLE VI of the Hellgate Treaty, providing for the allotment of lands to individual tribal members, and opening of reservation lands to settlement

- The 1908 amendment to the Flathead allotment act to build an irrigation project for the benefit of Indians and non-Indian settlers

- Valuable Walton, Secretarial, pre Hellgate Treaty and even pre-statehood water rights are effectively negated via ex post facto time immemorial water rights that preclude and diminish existing uses of water throughout western Montana.

- The promises made by the United States to every landowner via their land patents and water rights

- More than 100 years of established Winter’s Doctrine federal reserved water rights and other associated case law.

- Our constitutionally secured rights to due process and equal protection under the law

- To effectuate an unconstitutional taking of water and property rights without consideration or compensation.

- Violates the U.S. Constitution’s promise of a republican form of government to the people, by placing a large number of citizens under a water management board that is controlled by an unaccountable tribal government.

The Flathead Compact: Ushering in a new era where quantification of tribal water rights is no longer required.

The compact’s creation of tribal reserved water rights explains why there was no quantification of the amount of water ceded to the United States / CSKT in the compact. The tribes reserved it all. Without any such quantification, it is difficult if not possible to understand the injury or harm caused to people’s existing water rights but more importantly there is no need to quantify the tribe’s rights to all of the water because they “reserved all of it” from time immemorial.

Over the years, the compact commission often told us we never had the water rights in the first place. Think about that statement. What that means is that we did not have the water rights, because the compact ceded all of the water to the tribes. This also explains why the compact commission made a point to tell the public that they were working diligently to “protect existing uses of water.”

It was only necessary for the commission to protect existing uses of water because the tribe’s “compact awarded water rights” present a serious threat to existing state based uses of water.

Imagine the power and control this concession by the state gave to the tribe in what can only be seen as “bad faith” negotiations that took place over three decades.

The commission’s statement also implies that the compact effectively makes state based water users and landowners out to be squatters that have been using water that the “compact retroactively says” legally belongs to the U.S. and tribal government.

It also explains compact commission attorney Jay Weiner’s 2011 response to the Clark Fork Basin Water Management Taskforce when asked about the quantification of the tribe’s water rights:

COMMENT – I have heard a rumor that the compact will not quantify the CSKT reserved water right. Without quantification, I am unsure how adverse affect will be determined.

QUESTION – Will the compact specify or cap the flow and volume of the CSKT reserved water right?

ANSWER BY JAY WEINER – Maybe. This is a complicated issue. IF THE RESERVED RIGHT IS QUANTIFIED NUMERICALLY (either by volume or flow rate), IT WILL LIKELY BE LARGER THAN THE AVAILABLE SUPPLY. The Compact Commission will seek sideboards on the use of the reserved right to protect existing water users.

Indeed, rather than being landowners with bona fide water rights appurtenant to the land, the compact retroactively makes us mere “users of the tribal water right” subject to their Unitary Management Board and onerous terms and conditions.

Still Not Convinced?

At a compact commission meeting held in December of 2002, THE TRIBES DICTATED TO THE COMPACT COMMISSION THAT THEY WOULD QUANTIFY THEIR OWN WATER RIGHTS.

The subject of the meeting was the tribe’s 2001 proposal to the state of Montana, laying out the tribes negotiation framework. Keep in mind that the starting point for these “new and improved” negotiations began with the assumption that the state would acquiescence to the following demands:

- All water on and under the Flathead Indian Reservation is owned by the United States in trust for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

- The negotiation process will focus on the development of a comprehensive Reservation-wide Tribal water Administration ordinance, which will apply the seniority system and protect the unique federal attributes of Indian reserved and aboriginal rights.

- The Negotiations will also include other issues pertaining to the Tribes, reserved and aboriginal water rights. The Tribes possess off Reservation reserved and aboriginal consumptive and non-consumptive water rights that derive from their time immemorial use and habitation of vast aboriginal territory in Montana and elsewhere. To finally resolve all Tribal water rights within the jurisdiction of the commission the quantity of water necessary to protect the tribes off reservation rights in Montana must be determined.

When the commission attempted to push back on the tribe’s aggressive declarations about the quantification of the tribes’ water rights, a dialog ensued between Clayton Matt, the lead negotiator for the tribe and Chris Tweeten, chairman of the Reserved Water Rights Commission:

Chris Tweeten: Clayton, I don’t understand why it makes sense for the Tribes to go and unilaterally develop a proposal with respect to a quantification of water rights. Wouldn’t it be preferable to do that collectively and collaboratively in a negotiated process in which all three of the parties can have input rather than the Tribes come back and say, “we’ve done this work this is what we think now you take two years and go tear it apart and come back with your take on the same issue.” Don’t you think it will advance the ball faster if we do that jointly through the negotiated process rather than having the Tribes go and do it on their own and then come back and sort of give us a package that we can then either accept or reject, I’m not sure that’s going to be productive.

Clayton Matt: We proposed a solution and you’re not considering it and I think that this is our alternative and we don’t think it’s going to be any less fast than any of the other alternatives because I think within a couple years we can have a proposal on the table.

Chris Tweeten: Well, I’d like you to consider, let me find another word, I’d like you to think about whether it doesn’t make more sense for us to develop that quantification if that’s the route we’re going to take, collaboratively…

Clayton Matt: That’s the route the Tribe is going to take and I think what’s important about it and I want to make sure its really clear even if we take this approach the viability of the proposal in the Tribes mind and those elements of the proposal that I just described still make sense to us. We’re claiming ownership in the proposal you want to consider the proposal, fine. We’ll go off and quantify the right and even the State of Montana Supreme Court has said the Tribe owns its water. We’ll quantify that we own it. We have accomplished the same principal. We then have the opportunity to develop a water administration scheme for the administration of Tribal water resources. And we will do that and we will give very serious consideration to including existing uses. How we do that I think will be determined in the water administration package but if we can’t continue to get on with long-term negotiations based on this proposal we’re saying we need to get on with our settlement process and this is the alternative approach that we’re going to take and I think its time we get on with it.

Chris Tweeten: Well, I have serious concerns about whether that’s going to be a constructive way to approach these negotiations, frankly. Because I don’t think a series of solutions unilaterally developed by the Tribes and then placed on the table in the way you’re suggesting would be done, I don’t think that’s a process that is necessarily designed to or necessarily will produce consensus among the parties. It seems to me that’s designed to produce a series of almost ultimatums on the part of the Tribe saying you may take this proposal if you don’t like that we’ll give you another one and you can take that or leave it and I don’t think that’s…

Clayton Matt: Let’s step back here…

Chris Tweeten: Let me finish. I don’t think that…

Clayton Matt: And not paint the Tribe in a negative light here because it is not the Tribe that’s the bad guy here. We’re certainly not saying that anyone else is the bad guy here but you can paint your own picture; don’t paint our picture for us. We’re going to take the opportunity to do what state law says. State law says that these negotiations are settled Tribal water rights. Let’s go do it.

Chris Tweeten: You can obviously do what you want and how that fits into the process of negotiation I guess remains to be seen. I just want you to understand going in that speaking on behalf of the commission, I have serious concerns about whether that process is actually going to be productive, constructive and as to whether it’s designed to lead to the kind of consensus that we’re going to have to have to get a compact that has the support of the three negotiating teams, the support of the water users both Tribal and non-Tribal that are going to be affected by it and it can ultimately get the support of the Montana legislature, the congress and the Water Court. I think we need to keep in mind that this is a long process that has many steps…

Clayton Matt: Absolutely, but we’re defining the process and it is, as I said in our opening remarks, not our intent to hurt anybody so we’ll see where that goes because it’s not our intent to hurt the people here in this valley. In fact, we intend to work together with the people of this valley. So we just need to get on with it and we can’t continue to wait for you to be ready to consider our other proposal because that is the solution, that really is the solution. So that’s where we’re at.

Chris Tweeten: So is the outcome, Clayton, going to be that we either accept your original proposal or something that gets you to your original proposal or there won’t be a compact?

Clayton Matt: I don’t know. That’ll be for you to decide. We’re going to go quantify our water and bring the numbers to you.

Chris Tweeten: But from the Tribes perspective.

Clayton Matt: From the Tribes perspective we’re going to go quantify our water and bring the numbers to you.

Chris Tweeten: And what I’ve heard you say is that you’re going to quantify your water right in such a way as to reach the conclusion that all the water within the reservation belongs to the Tribe, is that correct?

Clayton Matt: Well, our proposal already says that.

Chris Tweeten: So, am I correct in understanding that after this two-year process that you’re going to follow to quantify your water right, you’re going to come back with a conclusion that all the water belongs to the Tribes?

Clayton Matt: You’re catching on.

Chris Tweeten: Well, I don’t know how that advances the ball.

Clayton Matt: I think how that advances the ball is that we get through the quantification of the Tribal right and we develop an administration scheme that we think is fair to everyone. What that looks like will be dependent on how we develop that. And if you want to join us in doing that, our proposal is on the table.

Chris Tweeten: Well, I guess…

Clayton Matt: If you don’t want to join us in doing that then we’re prepared to move forward and we just need to get on in doing that and if you want to paint the Tribe in some negative light that we’re out to hurt people here in this valley, go ahead and try. But we’re not there to do it.

Chris Tweeten: Clayton, nobody said that. I don’t think that’s a fair characterization of anything that’s been said this morning. So I…

Clayton Matt: We’re not here…

Chris Tweeten: Don’t think it helps to put the discussion in that context.

Clayton Matt: We’re not here to threaten the local water users. We are here to protect the water resources in the reservation and manage them. So that’s the reason we doing it. That’s it. And I think the United States supports the position in terms of at least as far as what you heard them say here a few minutes ago.

Chris Tweeten: We’ve also considered as the United States has, the legal basis of the Tribes proposal and frankly we disagree with the premise based on our review and our research and the study that we made of your proposal at the time it was put on the table. So there is a fundamental disagreement with respect to the underlying basis of the Tribes proposal.

Clayton Matt: We have a solution for getting to this, we’ve just offered it and I guess the next question is do you want to continue discussions on any of the other work items at this point because that’s where we’re headed in terms of the overall strategy.

Chris Tweeten: I think it’s probably appropriate to move onto the discussion of the interim plan at this point because I do think its important and actually the whole purpose of this meeting being held at this time was to inform the people in the community with respect to the status of those negotiations and to get input from the public with respect to the discussions that we’ve had on the interim plan.

CHECKMATE!

Last year we asked why didn’t Montana call off negotiations?

Let’s be a little more specific this year.

Why didn’t Chris Tweeten call off negotiations in December of 2002?

Was it due to Mr. Tweeten’s incompetence, ignorance, hubris, fear of the feds, or was something else in play at this moment in time?

While we may never have the answers, we do know that the state willfully chose this pathway for its citizens to have to walk.

It’s abundantly clear that in addition to ceding all of the water in western Montana and jurisdiction over it to the United States / CSKT, Montana also ceded its big boy pants at the negotiating table.

Pingback: Is The Flathead Water Compact Ex Post Facto Law? – Save Flathead Lake

In one fell swoop, the water and property rights rug was pulled right out from under the people who were counting on the state to protect its own interests and those of its citizens.

The compacting parties’ agreement to “tribe immemorial aboriginal water rights” retroactively ensures that there was no unconstitutional taking of the water and property rights of western Montanans because the compact says the water that we’ve been using for more than a century was reserved by and has always belonged to the tribe.

Does anyone really think that people would have purchased land and settled in western Montana had they thought that the tribe would own the water that is appurtenant to their property?

Such is the tyrannical nature of an Ex Post Facto law.

The Flathead Water Compact is a perfect example as to why a constitutional prohibition against ex post facto laws was necessary.

Pingback: Flathead Compact: Disconnecting Water from the Land | Western Montana Water Rights

Pingback: Twenty Five Years: The Delegitimization of Montana’s Adjudication Process | Western Montana Water Rights

Pingback: Article VI of the Hellgate Treaty | Western Montana Water Rights

Pingback: What is Res Judicata and Why is it Important? | Western Montana Water Rights