© 2023 Concerned Citizens of Western Montana

Once the dust has settled concerning which objectors will proceed forward to a Flathead Compact hearing, the court schedule tells us that the compacting parties will submit a motion to the Water Court requesting a ruling on the compact’s fairness and adequacy sometime in early or mid- July of 2024.

The Water Court has stated in various opinions on other compacts that it “has adopted the rule employed by the Ninth Circuit Court in reviewing consent decrees, which is that “once the court is satisfied that the [settlement] was the product of good faith, arms-length negotiations, a negotiated [settlement], is presumptively valid, and the objecting party has a ‘heavy burden’ of demonstrating that the [settlement] is unreasonable.”

This article questions any notion that the Flathead Compact was the product of good faith, arms-length negotiations by the compacting parties.

Good vs. Bad Faith

When most people hear the term good faith negotiations, it invokes an impression that such negotiations would be approached by all parties with honesty and without malice or the desire to defraud others.

Even the Montana legislature saw it that way when it created the Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission in1979:

85-2-701. ….. It is the intent of the legislature that the unified proceedings include all claimants of reserved Indian water rights as necessary and indispensable parties under authority granted the state by 43 U.S.C. 666 (McCarran Amendment). However, it is further intended that the state of Montana proceed under the provisions of this part in an effort to conclude compacts for the equitable division and apportionment of waters between the state and its people and the several Indian tribes claiming reserved water rights within the state.

Bad faith on the other hand “refers to dishonesty or fraud in a transaction. Depending on the exact setting, bad faith may mean a dishonest belief or purpose, untrustworthy performance of duties, neglect of fair dealing standards, or a fraudulent intent. It is often related to a breach of the obligation inherent in all contracts to deal with the other parties in good faith and with fair dealing.” Source: Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

April 2013: Compact Fails in the Montana Legislature

Leading up to the compact’s failure 2013, the compacting parties must have been certain that it would easily pass in the Montana legislature. After all, past experience told them that all previous compacts had passed the legislature with little if any opposition.

The commission’s talking point and informational pump was well primed. The commission did a masterful job of setting expectations and rationalizing the compact for the people that would be affected by it.

Influencers like the Clark Fork Commission task force members were told that if the tribe’s water rights were to be quantified, it would be more water than is available.

In meeting after meeting, the public was not told what the compact ceded to the tribe, and instead the parties conveyed that the tribe had ceded far more in the compact than they could have received in litigation.

The compact commission also frequently said that if the compact wasn’t ratified, everyone would have to hire an attorney to protect their water rights. We were also told quite often that we never had water rights in the first place. This effectively meant that it was the tribe alone that had rights to all of the water in western Montana.

And lest we forget, the Compact Commission assured people that “existing uses of water would be protected.”

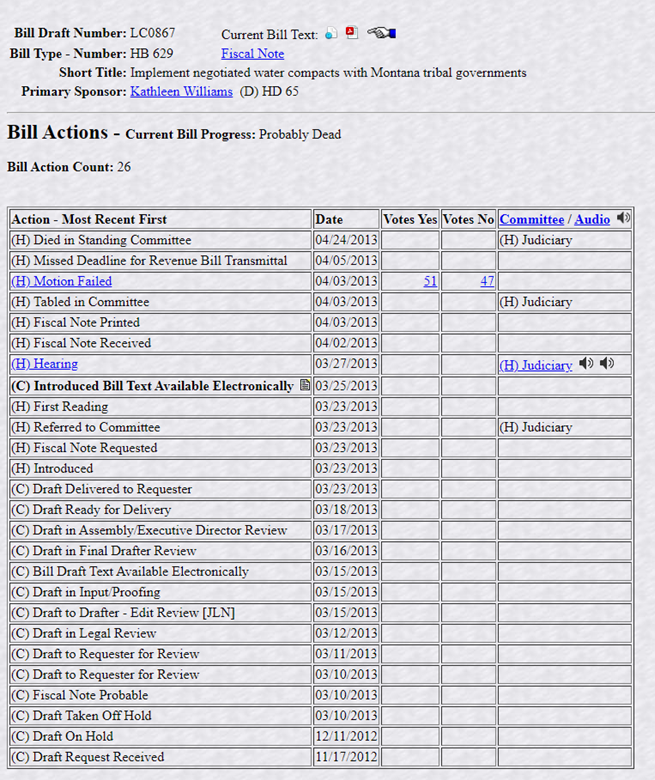

In March of 2013, Representative and seated Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission member Kathleen Williams, introduced Flathead Compact legislation HB629.

Her legislation included the controversial and unapproved Flathead Irrigation Project Water Use Agreement that mandated irrigators to withdraw and cease all defense of their water rights:

This Agreement and the Compact specify the terms under which the United States and the FJBC agree to withdraw and cease prosecution or defense of all claims to water, whether arising under Federal or State law, held in their names and filed in the Montana General Stream Adjudication, and whatever permits and other rights to the use of water recognized under State law that are held in their names for use on lands served by the FIIP. In exchange for withdrawal of all such water rights and claims, the CSKT commit to the use for irrigation and Incidental Purposes of the water right identified in Article III.C.1.a of the Compact (identified as the FIIP right) to be delivered by the Project Operator pursuant to the terms and limitations of this Agreement, including the Appendices.

Just a month before, in February of 2013, Judge CB McNeil issued a scathing ruling that the Flathead Joint Board of Control for the Flathead Irrigation Project, consisting of elected representatives of irrigators did not have the authority to enter into any agreement that:

- provides for the assignment of privately owned irrigator water rights to the tribes in violation of the Montana Constitution.

- contains no contractual agreement by the Tribes to issue any water right to any Irrigator whether designated “reallocated right” or otherwise.

- sends irrigators into a forum for disputes that deprives them of their Constitutional right to access to the state courts of justice and deprives them of the protection of their water rights by the Constitution of the State of Montana.

- contractually obligates irrigators to defend the Tribes’ application to the Water Court for all water rights on the reservation, in direct conflict with the Irrigators’ own right to apply to the Water Court to have their water rights adjudicated under Montana law.

Note: The McNeil decision did not address provisions in the agreement that would result in a 20-75% reduction in irrigation water deliveries compared to their historic uses of water. It also didn’t mention provisions for consensual agreements with the tribe that were referenced in the Water Use Agreement for the purpose of having irrigators acquiesce to diminished volumes of water and to prevent these lesser amounts from being called by the tribe.

How in the world could the MRWRCC push a compact that included such a harmful agreement for irrigators?

In April 2013, the Montana Supreme Court reversed Judge McNeil’s decision without addressing any of the legal or constitutional issues mentioned by Judge McNeil. This is because its decision was based upon a technicality in the Judge’s ruling. It’s important to remember that the compact has not yet been challenged on its unlawful and unconstitutional provisions.

Despite these efforts by the state to “save the compact”, it failed in committee and a motion to blast it to the House Floor failed, stopping the compact.

Shortly thereafter the compacting parties regrouped and came up with another strategy. Governor Bullock used an amendatory veto pertaining to SB265 to breathe life back into the compact and the irrigator water use agreement under the guise of preparing a report to “address the questions raised about the compact in the 2013 session.”

December 2013: The Governor’s Report is Issued

The Governor’s report, written and issued by Montana Reserved water Rights Compact Commission (MRWRCC) in December of 2013. True to form, the report did not address any of the serious flaws in the compact that caused it to fail in the legislature.

The Compact Commission instead used the report as an opportunity to expound upon their talking points, including the compact’s supposed “Protections for State Water Users.”

February 2014: CSKT Files a Federal Lawsuit

In February 2014 the CSKT filed a lawsuit against the Secretary of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, the State Water Court and District Courts, the Flathead Project Irrigation Districts, several named individuals and an unknown number of John Does.

In their prayer for relief, the tribes requested a declaratory judgment reaffirming and declaring that:

- the Hellgate Treaty did not implicitly diminish aboriginal water rights

- when the Flathead Indian Reservation (FIR) was created, the United States reserved all waters on, under and flowing through the Reservation for the Tribes;

- the chain of title to land on the FIR has never been broken and for that reason no lands within the borders of the reservation have ever been part of the public domain or subject to general public land laws;

- after the FIR was created the Tribes continued their exclusive and uninterrupted use and occupation of Reservation lands and waters for hunting, fishing and gathering practices, and that tribal water rights for non-consumptive aboriginal uses carry a priority date of “time immemorial.”

- all waters of the FIR for consumptive use were reserved by the Tribes pursuant to the Winters Doctrine.

- water rights on the FIR could only be acquired as specified by Congress.

- Congress specified the only manner for any non-Indian to acquire a water right on the Flathead Irrigation Project (FIP) in the Flathead Allotment Act (FAA) and subsequent acts, and that those conditions have not been met by any person;

- the Secretary of the Interior (SOI) has issued no person a “final certificate of water right” under the FAA;

- the 1904 FAA implicitly reserved to the United States out of the senior pervasive Tribal Winters rights a volume of irrigation water to serve the federal purpose of the FIP, with a priority date of April 23,1904;

- the BIA is entitled to a volume of irrigation water adequate to maintain beneficial irrigation in the FIP service area when such volumes of irrigation water are physically available within the FIR and do not adversely impact the Tribes’ “time immemorial” instream flow rights; and

- The FIP has always been a BIA Indian irrigation project and not a Bureau of Reclamation irrigation project.

There is absolutely no way to interpret this lawsuit except to understand that it was produced for the purpose of having a coercive effect on the legislature and the courts of the state of Montana. The goal was to use the lawsuit as a means of forcing legislative ratification and ensuring a positive judicial review of the compact in the Montana Water Court.

Word at the time was that the tribe was calling it a “narrowly tailored” lawsuit simply for the purpose of framing federal law pertaining the water compact.

As much as they tried to downplay it, one can easily see that it was meant to “encourage” legislative ratification of the compact, beat the irrigators into submission, and influence future actions of the district and water courts of the state of Montana.

We don’t know about you, but there clearly was nothing good faith about the tribe’s filing of this lawsuit.

The media was fairly silent about it, although we did see one article in the Missoulian. We also looked for any public comment made by the governor, the compact commission or the head of DNRC at the time, but found nothing.

Lawsuit? What Lawsuit?

A reasonable person might think that it would be a conflict of interest for the compacting parties to proceed forward while an active lawsuit pertaining to the very issues supposedly resolved in the compact were actively being considered in a federal court.

But based upon the actions of the compacting parties following the filing of the tribe’s lawsuit, such an assessment would be wrong. The three amigos proceeded forward as though the lawsuit did not exist.

The response by the compacting parties clearly shows to what extent they were willing to go to cram the water compact through the legislature and into the water court. It also demonstrates that the “negotiations” and actions of the compacting were not arms-length, nor were they in good faith.

Keep in mind, that by submitting the compact for consideration in 2013, the parties to the compact were already working in concert to mutually defend the compact from all challenges and attacks. This mutual defense provision is codified into ARTICLE VIII D. of MCA 85-20-1901.

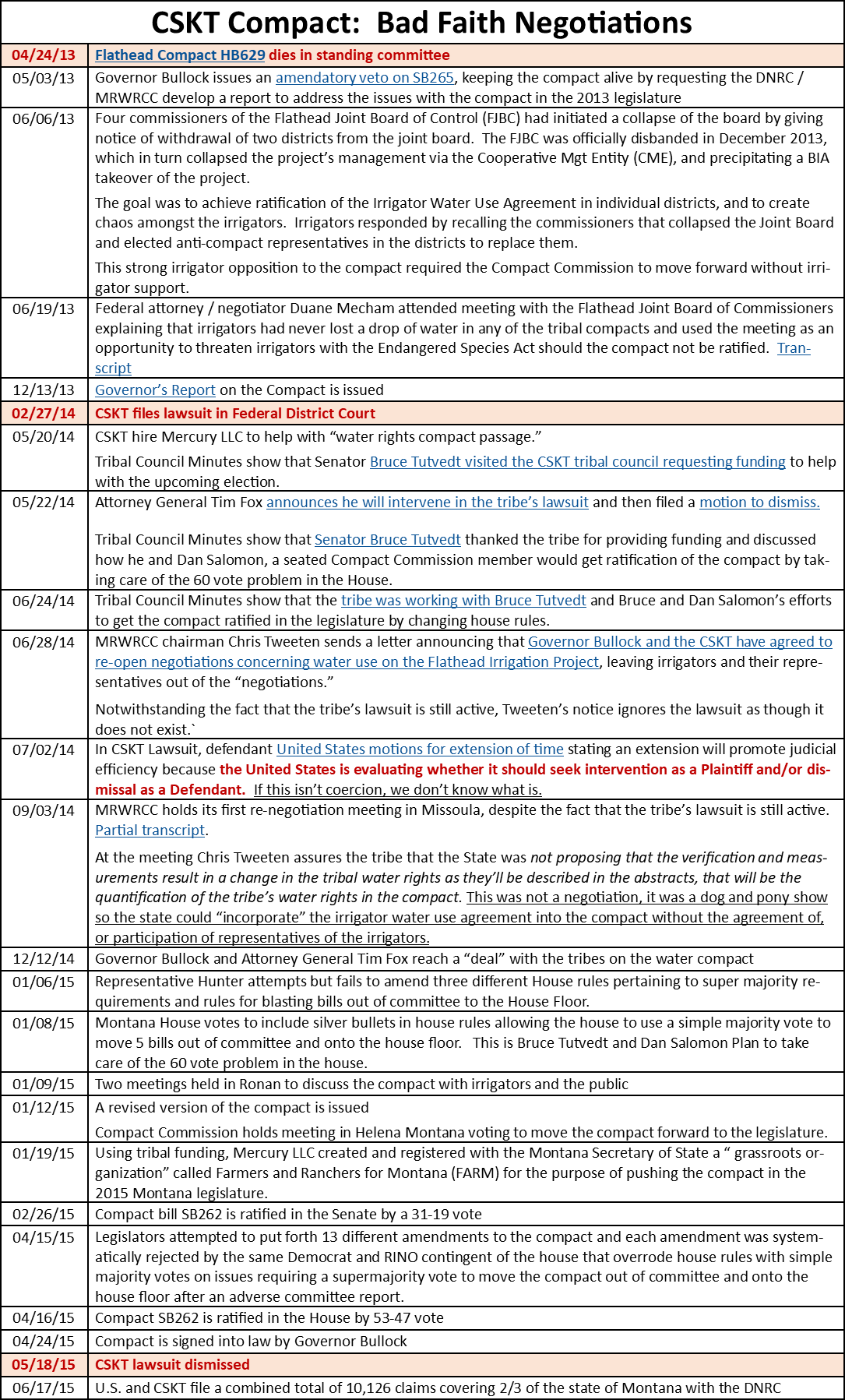

What follows is a chronological list of how the compacting parties responded to this very significant lawsuit that was filed on February 27, 2014, and dismissed fifteen months later on May 18. 2015.

(Click on photo below for a pdf copy of this timeline)

The fact that the compacting parties “re-negotiated, settled and ratified the compact” while an aggressive lawsuit by one of the compacting parties against the other two compacting parties was actively being reviewed and considered by a federal court gives new meaning to our question asking Why Didn’t Montana Call off Negotiations?

From the table above, you can see that the United States even went as far as to request an extension of time in July of 2014, to decide if it wanted to change sides in the lawsuit and become a plaintiff instead. Once again this shows the bad faith on the part of the United States and could only have been done to give a coercive message to the state of Montana and to the people resisting the compact.

Why didn’t Montana shut everything down? Because state officials were committed to the compact and in too deep to extricate itself from the hole it had dug itself into.

More Bad Faith: the 10,000 Claims

There is one more very important point that must also be made: If the tribe and the United States were acting in good faith when they filed their claims with the state of Montana in June of 2015, they would have only filed the claims that the three parties had agreed to in the Compact.

Instead they chose to aggressively file 10,126 claims covering 2/3 of the state of Montana as an insurance policy for Compact ratification in the legislature and the Montana Water Court.

This too can only be seen for its coercive intent, and that tact has already used by compact proponents ad nauseum.

Then in December of 2022, the state used the 10,000 claims in its brief to the water court that discussed the horrible effect the adjudication of the 10,000 claims would have all over the state if the compact was not approved by the water court. See: Have the Tribe’s 10,000 Claims Come Home to Roost?

It is also notable that there were two versions of the compact made pubic in 2015, one on January 7, 2015, and a second one released on January 12, 2015, the day that the compact commission voted to move the compact forward to the Montana legislature.

There literally was no time for the public to review the new version of the compact ahead of getting in our cars to drive to Helena for the compact commission vote.

We were curious about the changes, and later analyzed both versions of the compact for changes and discovered that someone inserted language in the January 12th version of the legislation pertaining to the filing of the 10,000 claims, and dismissing them WITHOUT PREJUDICE. Talk about BAD FAITH!

We can only imagine the state allowing tribal attorneys to revise the compact at the last minute hoping no one would take the time to look at their handiwork to maximize the coercive effect of the 10,000 claims.

This compact was supposed to bring finality. How could the state of Montana and its legislature allow this language to find its way into Montana Code Annotated?

There are trillions of dollars at stake here. The compacting parties have hedged their bets well.

The question now is whether objectors can convince the Water Court that the compact is not the outcome of good faith, arms-length negotiations.

The compact’s ugly details are a mirror image of the deceitful strategies and tactics used by the compacting party amigos to move the compact through the process.

Re: “the Hellgate Treaty did not implicitly diminish aboriginal water rights”

No, it DIRECTLY diminished aboriginal water rights by extinguishing all rights, title, and interest to aboriginal lands.

Absolutely agree.

Indeed the treaty extinguished all right title and interest to the lands so ceded, including water. Even the tribe’s attorney that wrote that lawsuit understands that this was the intent of the United States via the treaty.

While this article does not specifically address any of the ridiculous declaratory demands in the lawsuit, suffice it to say every one of them can and would have been defeated had the lawsuit not been dismissed just in time to be replaced by the threat of 10,000 claims.

Has the 10,000 threat claim been removed from this agreement? I am sick of legislators that legislate by fear. Make certain it is null and void. This whole Compact is thievery of non-native water rights and a woke farce.

The 10000 claims are not part of the compact except to the extent that the compact says they will be dismissed without prejudice.

Should the compact be voided by the water court or defeated in another court of law, the 10000 claims will rear their ugly heads and will either need to be adjudicated by the state of Montana or the compacting parties will try to have them decreed in federal court.

I know it isn’t IN the Compact but has it been written that the tribe will NOT do it anyway even if the compact is not voided? I still can’t believe this compact has gotten this far. It is so wrong, unfair & unconstitutional to the citizens of MT. Everyone responsible for not fighting this because it will end up in court, should be ashamed.

Agreed.

One of the worst things about this is that the compacting parties continue to count on the fact that people went to sleep because they were told their uses of water are “protected”. We fully expect that this “your water rights are protected” tactic will be used against most of the objectors in good time.

What people don’t seem to understand or care about is if we allow government to cause great harm to irrigators, or remove more than 30,000 of its citizens from the protection and control of the state and its courts, it will be empowered to do it to others.

As for non-objectors, most will never question why their water rights would need to be protected from the tribe at all?

The language in the compact pertaining to the dismissal of the 10000 claims without prejudice was inserted into the 1/12/15 version of the compact by someone at the very last minute just before the compact commission’s vote. Talk about BAD FAITH!

The whole darn compact is about the United States and federal attorneys exploiting federal Indian policy for the purpose of restoring federal ownership and control over the water of western Montana. People will only care about it when it affects them directly.

The Daines legislation purports to have fixed the “without prejudice” language in the compact, but it remains in Montana statute, unable to be amended unless the tribe gives the state “permission” to amend. How does that scenario work under the laws and the constitution of the state? It doesn’t.

We also believe that while the Daines legislation appears to fix the “without prejudice” language, it includes other provisions within the bill that negate that “fix”.

Posting this comment from our friend Christopher:

Two items … both quotes below from the article.

Even the Montana legislature saw it that way when it created the Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission in 1979:85-2-701.

“….. It is the intent of the legislature that the unified proceedings include all claimants of reserved Indian water rights as necessary and indispensable parties under authority granted the state by 43 U.S.C. 666 (McCarran Amendment). However, it is further intended that the state of Montana proceed under the provisions of this part in an effort to conclude compacts for the equitable division and apportionment of waters between the state and its people and the several Indian tribes claiming reserved water rights within the state.”

McCarran Amendment: 43 U.S.C. 666. Note that this is U.S. Code, not MCA Montana code. Thus the underlying law of the Compact Commission was stipulated as McCarran Amendment.

The first item has to deal with the “underlying law” with regard to the formation of the Compact Commission, both of which are looking for authority within MCA 1979: 85-2-701 (creation of the compact commission via Montana legislature); and in a deeper reach within federal law 43 U.S.C 666, specifically the McCarran Amendment. It would seem in the two sections below that Montana hung the hat of the Compact Commission on the hat rack of the McCarran Amendment, to the exclusion of other pertinent law, if any. It bears repeating: If any.

Thereby it is quite easy to assume that the factual underlying law, for the Compact Commission should and would lie within the McCarran Amendment. Notwithstanding anything that happened within the other 18 compacts (seven tribal, and eleven other {maybe} relevant non-tribal, including the federal forest service), the CSKT Compact is a bird that flies with a lot of different colored feathers that can not claim DNA from any other compact; and its flight wings are all non-McCarran.

It is perhaps that all these varied compacts lack a fundamental underlying basis (law), as they also ‘wandered’ away from the McCarran Amendment. I do wish to speak to that. Only with regard to the funny non-McCarran bird known as the CSKT Compact and its ramrod federal legislation, that also does not build upon the McCarran Amendment, in attempts to build upon the falsity of the Compact SB262, re: 2015.

For any law to pass constitutional muster, it must avoid the dagger to the heart, of the canon of unconstitutional vagueness, which states that any law too convoluted for the average person to understand, is deemed unconstitutionally vague, and thus null and void. To this author, it is way beyond my understanding, and I have no firm knowledge of what, if any, underlying law, might be applicable; and to this author, the Compact is not a McCarron Amendment legal edifice. Thus might not the Compact be patently unconstitutional, but also the process by which it devolved, as it evolved not upon the basis of McCarran.

If there exist any other underlying law, we should know that, and after better than 10 years of distractive obfuscation, we don’t. A non-lawyer such as I, do not. This begs the argument that all that has transpired, has no citable underlying law, and thus again by default, vague and not understandable by the average person. Non-McCarran, patently vague, not understandable. Unconstitutional. Not within the bounds of a constitutional republic. What more should be said?

Second Item:

In April 2013, the Montana Supreme Court reversed Judge McNeil’s decision without addressing any of the legal or constitutional issues mentioned by Judge McNeil. This is because its decision was based upon a technicality in the Judge’s ruling. It’s important to remember that the compact has not yet been challenged on its unlawful and unconstitutional provisions.

Notwithstanding the machinations of the Compacting Parties (the trilogy of ‘governments’), none have made it clear as to be understandable, on a constitutional basis. None. Just who was participating on behalf of the average person … citizen of Montana? The Montana legislature shirked its responsibility in all these regards, and bifurcated it citizenry as to legislature, judicial, and even executory function, and placed that in a combined function of a Grand Bargain usurpation, in legal usury, a loan, of inexacting magnitudes, from time immemorial until perpetuity, never for the state to regain its wholeness and its lost integrity. A loan that can not be paid, or from which one can not be extricated. The reason for resorting to such bifurcation, to date, is unreasonable, only to be hidden in a political fog, though may play out in the future to further separate the public from the government, whereby this compact is a notable start.

All of this in spirit is unconstitutional, and in law is flauntingly unconstitutional, in ways so many, as to only add to the abject unconstitutional vagueness, to further tar this pathetic off-spring of usurpation.

For any court to look at, and understand these falsities (and they do!), is unconscionable. The Water Court must declare the Compact unconstitutional for a myriad of reasons, that should not have to be detailed before it.