© 2024 Concerned Citizens of Western Montana

NOTE: We are not attorneys, and the information in this article is not intended to give legal advice to anyone. As an objector to the Flathead Compact, only you can decide what pathway you must follow to protect your specific interests and rights.

As a reminder, Water Court Case Management Order Number 3 establishes this upcoming schedule for Motions regarding Compact adequacy and fairness, and any other issue(s) of law that does not require the Court to make findings of fact.

- Motion deadline: July 10, 2024

- Answer briefs: August 23, 2024

- Reply briefs: September 6, 2024

- Oral argument: September 19, 2024

At this juncture, objectors are faced with a choice to either proactively file a motion with the court for the purpose of getting their issues out front, or to wait and respond to the Compact parties allegations and claims.

Objectors are not required to file a motion on or before the July 10th deadline, but some objectors might be planning to do so. The decision to file a motion is completely up to the individual objector or objectors.

Whether you proactively file an offensive motion or not, you will still need to respond to any motion, and each of the allegations made by the compacting parties in what will very likely be motions pertaining to the compact’s fairness and adequacy, and for dismissal of objectors for lack of standing and other various reasons.

Any other issue(s) of law that does not require the Court to make findings of fact

We’ve found that clarification has not really been a strong point for the water court. While much of the information in the Court’s orders might be clear to attorneys, pro se folks often seem to be left scratching their heads with respect to some of the language that is used by the court.

Case Management Order #3 provides a July 10th deadline for parties to file Motions pertaining to Compact fairness and adequacy and any issues of law that do not require the court to make findings of fact.

Aren’t findings of fact what courts are supposed to do?

We think that this choice of words by the Court may be because the Compact is being reviewed as a consent decree and the water court has already stated that “Neither the water court or trial court is to reach any ultimate conclusions on the contested issues of fact and law which underlie the merits of the dispute.”

We must not lose sight of the fact that the goal of the compacting parties is to get the Compact all the way through the legislature and courts of the state of Montana without the details of their “forever settlement” ever being reviewed on their merits, facts or issues.

This post addresses one such legal issue that could be presented to the court as a motion for summary judgment pertaining to a legal issue that does not require the court to make findings of fact, because two other courts have already adjudicated these issues, and made findings of fact and conclusions of law pertaining to CSKT ceded lands.

Res judicata is a principle most used in civil litigation.

Directly translated, res judicata means “a matter judged.” Specifically, the res judicata principle indicates that if there is a final judgment based on merits, then another plaintiff cannot relitigate the same matter for the same cause of action. The court uses the term “finality” to indicate a judgment that is based on merits and is final. To be adjudicated based on merits refers to the ruling, judgment, or decision that the court makes after all the proper procedures of the trial. The court must also review and evaluate all the relevant materials and evidence regarding the trial at hand. Traditionally, res judicata only applied to cases that the court decided based on the merits.

Source: Legal Information Institution, Cornell Law

Definition of PRECLUDE:

- To close; stop up; shut; prevent access to.

- To shut out; hinder by excluding; prevent; impede.

- To prevent by anticipative action; render in-effectual or unsuccessful; hinder the action of.

- Synonyms To prevent, bar, debar, prohibit.

CSKT grievances and settlements

Section 22 of the Indian Claims Commission Act, ch. 959 60 Stat. 1055, 25 U.S.C. (1976 ed.) 70u, /1/ provides:

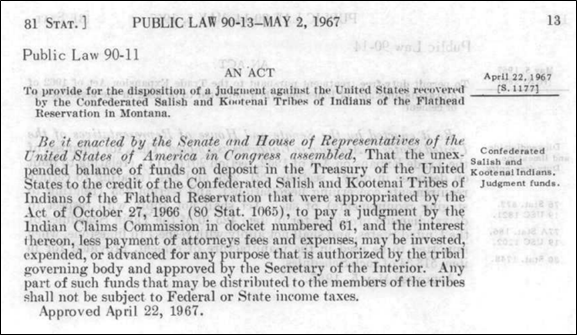

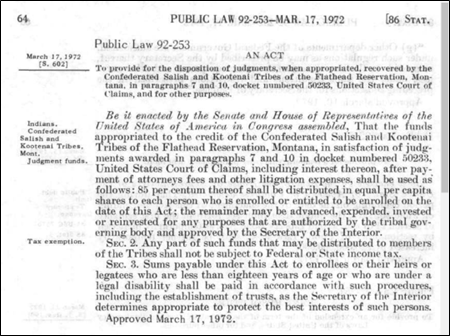

(a)When the report of the (Indian Claims) Commission determining any claimant to be entitled to recover has been filed with Congress, such report shall have the effect of a final judgment of the Court of Claims, and there is authorized to be appropriated such sums as are necessary to pay the final determination of the Commission. The payment of any claim, after its determination in accordance with this (Act), shall be a full discharge of the United States of the claims and demands touching any of the matters involved in the controversy.

(b) A final determination against a claimant made and reported in accordance with this (Act) shall forever bar any further claim or demand against the United States arising out of the matter involved in the controversy.

Source: Brief of the United States, USA v. Mary Dann and Carrie Dann, SCOTUS Docket 83-1476

It should be noted that any judgments and settlements pertaining to the US Court of Claims have the same preclusive effect.

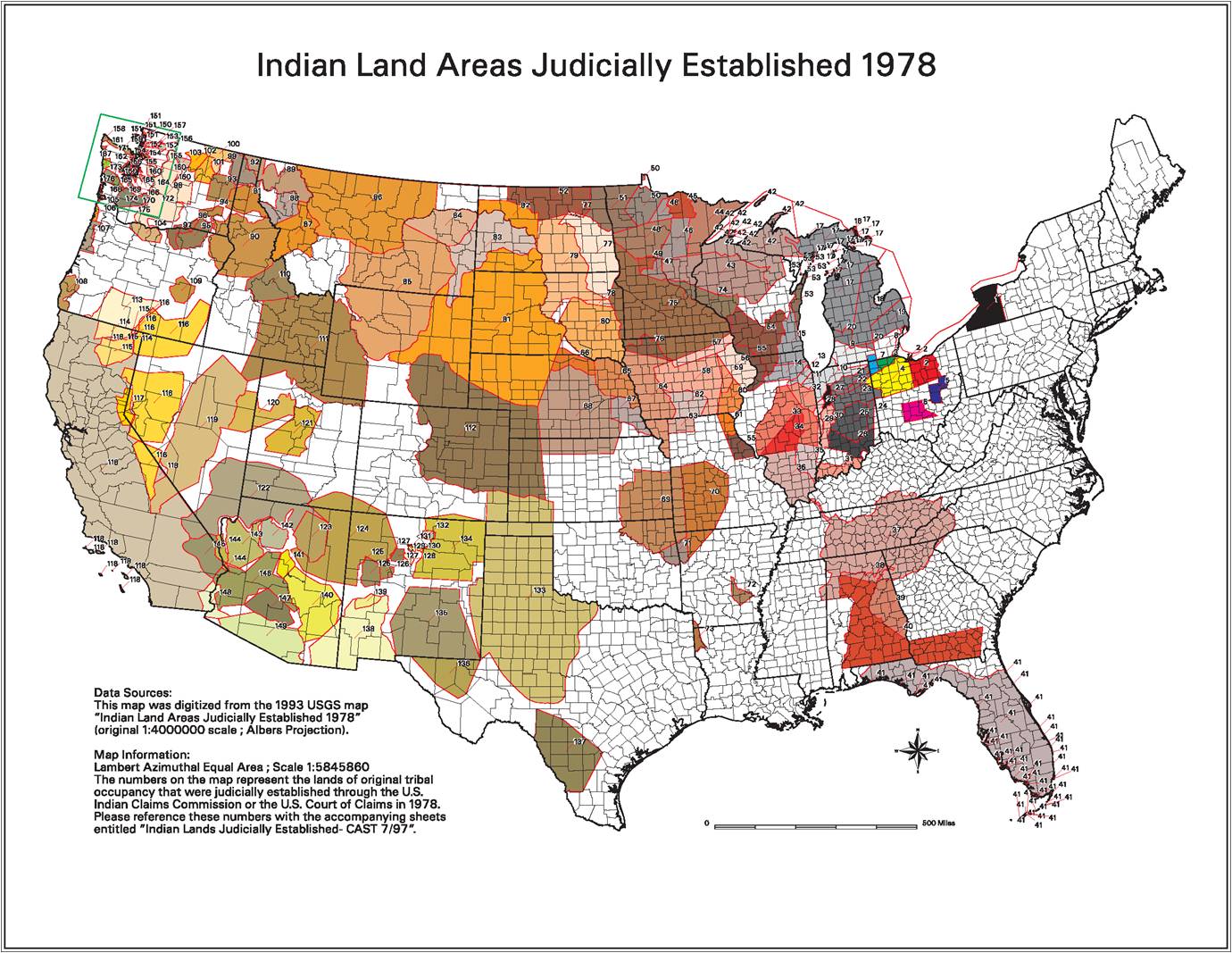

Indian Claims Commission Docket 61: off reservation aboriginal title claim

In 1950 the CSKT filed a complaint with the Indian Claims Commission pertaining to its “off reservation ceded lands.” The tribe claimed that the payment received from the United States for the lands ceded was unconscionable.

Over the next 16 years a rigorous trial took place to determine the effective date of the treaty (March 8, 1859), the acreage and value of the land ceded by the tribes (~12 million acres), and to make a determination as to the reasonableness of the payment made to the tribes by the United States.

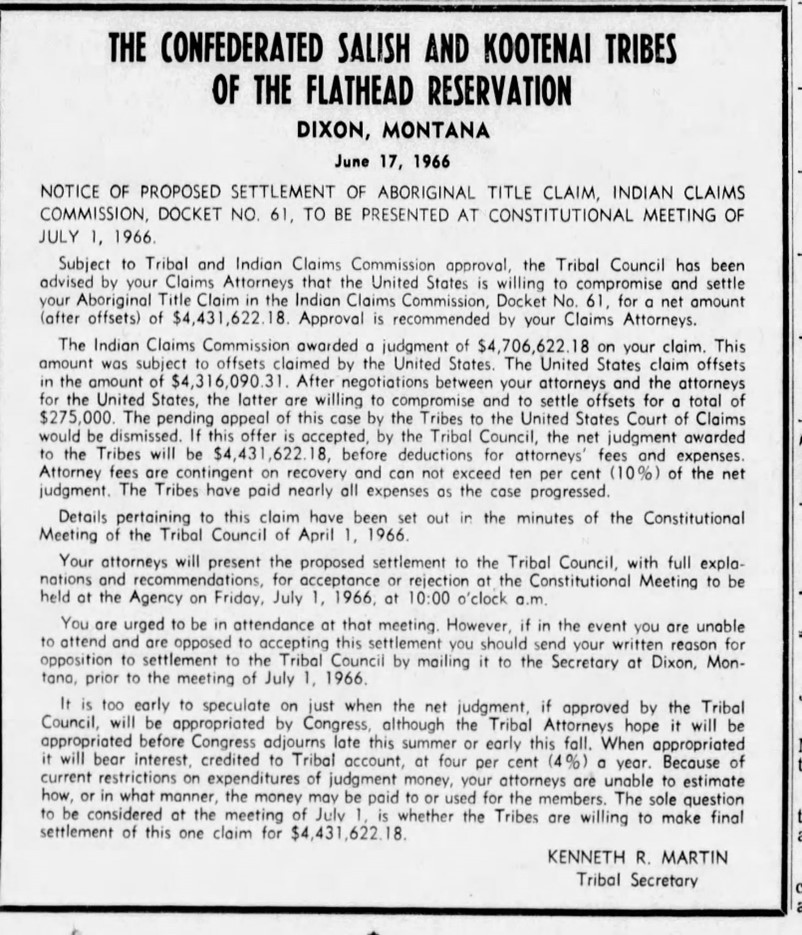

In 1965 the court determined that payment was unconscionable and that the tribes be awarded an additional judgment of $4.7 million before offsets such as legal fees. In 1966 the proposed settlement was taken to the tribal membership, and was approved by a majority of respondents. The CSKT Tribal Council unanimously voted to accept the settlement.

The parties entered into a stipulation agreement for final judgment that included the following condition: “The judgment shall finally dispose of all claims or demands which petitioner has asserted or could have asserted in this case against defendant, and petitioner shall be barred from asserting all such claims or demands in any future action.”

On April 22, 1967 Congress approved payment of this settlement.

It is important to note that 75% of the funds were distributed per capita to individual tribal members and 25% was retained by the tribal council government. This means that both the tribal council and individual members accepted and are bound to the terms of the settlement and the stipulation agreement.

US Court of Claims Docket 50233: on reservation claims

In 1951 the CSKT filed a complaint in the US Court of Claims (Docket 50233) pertaining to a number of grievances. The complaint included a claim of takings pertaining to on reservation lands taken as a result of the opening of the reservation to settlement (Paragraph 10 of the complaint).

Over the next 20 years, each grievance was resolved by the court with the exception of Paragraph 12 to what the tribe called a taking of water on the Flathead Irrigation Project, which was dismissed without prejudice in 1964.

The Paragraph 10 complaint pertaining to reservation lands followed a similar path as Docket 61, and in 1971 the Court of Claims issued a ruling finding that the lands taken by defendant, within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment, plaintiffs are entitled to recover the difference between the fair market value of the said lands as of January 1, 1912 and the compensation therefore previously received by plaintiffs, or a total of $6,066,668.78, plus interest. With interest the total settlement was $22.4 million dollars.

See: CSKT ICC and Court of Claims Settlement Summary

On March 17, 1972 Congress approved payment of this settlement. 85% of the settlement funds were distributed per capita to each individual member and 15% was retained by the tribal council government. Once again both the CSKT tribal government and the CSKT tribal members accepted the terms of the settlement for their on reservation claims.

See: House Report 92-696

Why this History is Important

First and foremost, the language of the Indian Claims Commission legislation clearly shows that Congress intended that the grievances of tribes would be settled with finality. Yet in 2024 in the case of the CSKT, we are still litigating the same issues that the Indian Claims Commission and United States Court of Claims resolved with finality decades ago.

In each of these two cases, the Court went through the painstaking process of determining the validity of the tribes claims by establishing their aboriginal title to the lands in question, reviewing the facts and historical record, and completing an appraisal of the value of the lands. Each party completed its own analysis and appraisal for submission to the court for consideration.

The land was classified and appraised based upon its characteristics: agricultural, grazing, timber, wasteland, and water. Any structures and improvements to the land as of the selected dates was also taken into consideration.

Each trial was determined and decided upon findings of fact and conclusions of law.

The United States acknowledged Aboriginal title to the Salish and Kootenai Tribe’s ceded land in the treaty of Hellgate, and the processes in both the Indian Claims Commission and United States Court of Claims confirmed it.

When payment was accepted by the tribal government and the individual tribal members via a per capita distribution in both cases, the tribe’s aboriginal title was extinguished.

In fact, here is a copy of the notification for tribal members that was published in the Montana newspapers asking tribal members to approve the Indian Claims Commission settlement in Docket 61 or off reservation ceded lands. It clearly noted that it was a settlement of ABORIGINAL TITLE CLAIM:

This is probably why CSKT Vice Chairman E.W. Morigeau testified to members of the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs at a 1979 Congressional Field Hearing held in Ronan concerning United States v. Abell, a lawsuit filed by the United States for tribal and other federal reserved water rights throughout western Montana. Mr. Morigeau said this:

I would like to set the record straight. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Council has never claimed water or water rights outside of the border of the reservation.

Concerning Claims within reservation boundaries he said this:

The way the complaint is written it is mighty confusing, as after examining the complaint filed in April, I find there are only six water users within the entire Flathead Reservation named as defendants, using tribal water without а water right….

……Four of the nine water users within the reservation named in the complaint were there by error and have been notified of such, leaving six and including the state of Montana.

The Indians knew that their aboriginal title to those lands had been extinguished.

The multi-billion dollar question is, Why didn’t the Compact Commission and Steve Daines know it and provide for a settlement that reflected this legal reality?

How is it possible that the tribe is able to retain time immemorial water rights on land it ceded all right, title and interest in, and its aboriginal title was extinguished decades ago?

Unfortunately Montana is attempting to make this possible in the CSKT Compact.

As far as the on reservation Court of Claims case, the same arguments can be made.

In that case, the court ruled that the United States had effectuated an Article V takings of CSKT land within reservation boundaries when it opened the reservation to settlement via the Flathead Allotment Act. When the Court of Claims settlement was paid for those lands, Indian title to the lands in question was extinguished.

1980-2014: The CSKT Negotiate a Water Rights Settlement with the United States and State of Montana

We have little doubt that legislature and the people of Montana expected the Compact Commission to complete its due diligence with respect to each tribes’ history and situation in preparation for the negotiation process.

The Flathead Reservation situation is complicated specifically because it was the only reservation in the state opened to settlement after allotment.

Within reservation boundaries, water rights issues are quite complex with the existence of Walton Rights, Secretarial Rights, Federal Irrigation Project Rights and other state based water rights to name a few. Montana knew the situation was complex, because it was documented in the transcripts of the minutes of the Compact Commission meetings.

But instead of quantifying the tribes federal reserved water rights as mandated by the Montana Supreme Court in the Ciotti decisions, the Compact Commission agreed to a water rights free for all by agreeing to the creation of ABORIGINAL time immemorial “tribal reserved water rights” outside of and within reservation boundaries for the purpose of fish and wildlife.

Not one drop of water in the compact was set aside for the needs of the tribe or tribal members… which is a fundamental component of a federal reserved water rights settlement.

To this day, the state has refused to provide a quantification of the amount of water awarded to the United States / CSKT in the compact, so the public could see what if any surplus water still exists for use in western Montana, or even if enough water exists for their own water rights.

So here is the deal, if Montana had completed its due diligence, it had to have known that the tribe is precluded from going after any water outside of reservation boundaries. Under the Winters Doctrine, the tribe only had valid claims to a discrete amount of water necessary to fulfill the purpose of only those lands that still remain in trust for the reservation (in other words, a diminished reservation).

Here is the language of the stipulation agreement once again.

The judgment shall FINALLY DISPOSE OF ALL CLAIMS AND DEMANDS WHICH PETITIONER HAS ASSERTED OR COULT HAVE ASSERTED IN THIS CASE AGAINST DEFENDANT, and PETITIONER SHALL BE BARRED FROM ASSERTING ALL SUCH CLAIMS AND DEMANDS IN ANY SUCH FUTURE ACTION.”

Montana agreed to a compact that completely ignores the fact that the tribe was paid for their ceded lands both outside of and within reservation boundaries and are precluded from going after the water associated with those lands.

If the Commission didn’t do its research on these issues, then they were negligent in their duty to the state and to its citizens.

The reason for this “oversight” by the Compact Commission, state leadership and legislators, is either FRAUD perpetrated upon the people of Montana, or it is NEGLIGENCE.

We believe it is the former.

2014: The CSKT File Lawsuit Seeking a Declaration of Ownership of all Reservation Water and to Cloud title to all privately owned land within reservation boundaries

Less than a year after the Flathead Compact failed in the 2013 Montana legislature, the CSKT filed a lawsuit against the United States Secretary of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Flathead Irrigation Project Districts, Montana’s 20th District Court and Water Court, several individuals, and an unknown number of John Does.

The tribes’ prayer for relief displayed the fact that the tribe was attempting to circumvent the state adjudication process essentially by asking the court to declare tribal ownership of all of the water within reservation boundaries and a declaration that the tribe has unbroken chain of title to the lands. In other words, that they still have aboriginal title.

Mountain States Legal Foundation represented four individuals named in the lawsuit. In part, their response to the tribes’ complaint noted:

In Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes v. United States, 437 F.2d 458 (Ct. Cl. 1971) (this is Docket # 50233), Plaintiffs brought a Fifth Amendment takings claim against the United States regarding surplus lands within the Reservation that had been patented to settlers. Plaintiffs were awarded just compensation for the value of those lands, including “all homestead and cash entries[.]” Id. at 469, 471; Compl. ¶ 48 (citing Confederated Salish, 437 F.2d at 458) (“The [Flathead Allotment Act] has been judicially determined to have been an unlawful breach of the Hellgate Treaty.”).

Interestingly, Plaintiffs now claim continuing title to those same lands, including those patented to Landowners’ predecessors, for which they received just compensation in Confederated Salish. See Compl. ¶ 56, Count One ¶ 8, Prayer for Relief ¶ 3 (“[T]he chain of title to land on the [Reservation] has never been broken and for that reason no lands within the borders of the [Reservation] have ever been part of the public domain subject to the general public land laws.”).

This is because of the preclusive effect of Confederated Salish, Plaintiffs’ claim of continuing title to the lands patented to settlers is barred by res judicata.

For more information see these documents from that case:

- CSKT Amended Complaint

- MSLF Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss

- CSKT Response to MSLF Brief

- MSLF Response to the Tribes Response

Why is this information important?

If you live in western Montana, whether it be outside of, or within the boundaries of the reservation, this tribe has settled its claims and is bound by the terms of the settlement and the stipulation agreement. Their aboriginal title to those lands was extinguished upon acceptance of their financial settlement.

To reiterate the stipulation agreement in Docket 61 is abundantly clear:

The judgment shall finally dispose of all claims or demands which petitioner has asserted or could have asserted in this case against defendant, and petitioner shall be barred from asserting all such claims or demands in any future action.”

It is not okay for a tribe, the United States or a State to create a new legal theory decades later for the purpose of reopening grievances that were legally resolved long ago.

As it is structured, the compact effectively imposes upon the people ex post facto law that undermines private property rights, the constitution, and existing federal reserved water rights law.

If the compact is allowed to stand, it will have far reaching implications for everyone living within the ceded territories of tribes throughout the western United States.

The CSKT settlements DISPOSED OF ALL CLAIMS OR DEMANDS WHICH THEY ASSERTED OR COULD HAVE ASSERTED AND THE TRIBE IS BARRED FROM ASSERTING ALL SUCH CLAIMS OR DEMANDS IN ANY FUTURE ACTION.

This is important information that needs to get in front of the Water Court and we believe the Court has provided objectors with an opportunity to do so in the upcoming motions phase of the proceedings.

Because the tribes’ settlements are “settled law” and the findings of fact in both the on and off reservation cases have already been determined it seems to fit the Water Court’s requirement of not requiring the Court to make findings of fact.

The compact ignores res judicata and must be voided.

We urge all objectors to consider including this information in their upcoming motion if they plan to prepare and submit a motion for summary judgment to ask the water court to void the compact.

Stay tuned for a few more ideas pertaining to motions to the court.